Here’s a wonderful review of Middle of Nowhere from Nikki Tate, B.C. books reviewer for the CBC radio afternoon show All Points West. Thank you once again for your support, CBC! Listen here.

Here’s a wonderful review of Middle of Nowhere from Nikki Tate, B.C. books reviewer for the CBC radio afternoon show All Points West. Thank you once again for your support, CBC! Listen here.

Here’s a wonderful review of Middle of Nowhere from Nikki Tate, B.C. books reviewer for the CBC radio afternoon show All Points West. Thank you once again for your support, CBC! Listen here.

Here’s a wonderful review of Middle of Nowhere from Nikki Tate, B.C. books reviewer for the CBC radio afternoon show All Points West. Thank you once again for your support, CBC! Listen here.

Both Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week and Middle of Nowhere made The Next Chapter’s Children’s Book Panel list of summer reading recommendations. Thank you CBC! Read the whole list here.

Both Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week and Middle of Nowhere made The Next Chapter’s Children’s Book Panel list of summer reading recommendations. Thank you CBC! Read the whole list here.

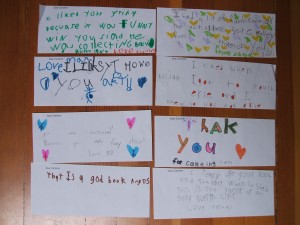

I agree with Jasper John Dooley: it’s wonderful to receive compliments! I thank the kids from The Mabin School in Toronto for sending these…

I agree with Jasper John Dooley: it’s wonderful to receive compliments! I thank the kids from The Mabin School in Toronto for sending these…

Here’s a neat-o feature from the Children’s Writers and Illustrators of BC blog. Thanks for asking, CWILL!

Here’s a neat-o feature from the Children’s Writers and Illustrators of BC blog. Thanks for asking, CWILL!

![]()

I enjoyed this thoughtful post from LiterariTea comparing childISH and childLIKE protagonists in children’s literature. In the childLIKE corner: Jasper John Dooley! Read it here.

I enjoyed this thoughtful post from LiterariTea comparing childISH and childLIKE protagonists in children’s literature. In the childLIKE corner: Jasper John Dooley! Read it here.

What a fabulous time I had during Book Week! I’d like to thank all the teachers and librarians who helped make my tour a success, the Canadian Children’s Book Centre for running such a fantastic program for the last thirty years, and TD Canada Trust and the Canada Council for supporting it financially. Especially, I want to thanks the children of Ottawa, Osgoode, Carp, Toronto, Collingwood, Meaford and Thornbury. You were just about the nicest bunch I could ever hope to meet!

Here I am with the kids of Connaught Public School in Collingwood, Ontario, gathered around Earl, Jasper John Dooley’s wooden brother. The kids assembled Earl during the presentation.

Here I am with the kids of Connaught Public School in Collingwood, Ontario, gathered around Earl, Jasper John Dooley’s wooden brother. The kids assembled Earl during the presentation.

And here are the Connaught kids performing their Symphony of Body Sounds with me conducting.

Here I am signing books next to Jasper John Dooley’s Family Stick.

Soon I’ll be doing school presentations for my latest book Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week. In the story Jasper, who is an only child, decides that his family is too small and sets out to make himself a brother out of wood. This idea came from real life. When my son was in Grade One he also made himself a wooden brother with help from his grandpa. Like Jasper, my son brought his wooden brother to school and presented him as his “Montre et Racontre” (French Immersion Show and Tell). Here he is:

This was the wooden brother I had in mind when I was writing Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week, with one difference. In the book the wooden brother, Earl, has “a purple face”.

The illustrator of Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week, the wonderful Ben Clanton, had a different Earl in mind. Since my son’s original wooden brother is precious to me, not to mention a bit fragile (you can see he has already lost an arm!), I decided to make a new wooden brother that looked more like the one Ben drew. I also decided I would make Earl the way Jasper made him in the book, using only materials I already had. This is how I made the Earl who will be visiting schools with me.

1. I found some wood scraps.

1. I found some wood scraps.

2. I cut out pieces of Earl using Ben Clanton’s design.

2. I cut out pieces of Earl using Ben Clanton’s design.

3. I attached Earl’s feet to his legs and neck to his body with screws.

3. I attached Earl’s feet to his legs and neck to his body with screws.

4. In the book, Ben Clanton draws Earl unpainted. (Ben, you didn’t read very carefully! Earl has a purple face!) I primed Earl first, which means I painted him completely white.

4. In the book, Ben Clanton draws Earl unpainted. (Ben, you didn’t read very carefully! Earl has a purple face!) I primed Earl first, which means I painted him completely white.

5. Since I had to paint Earl’s face purple, I decided his arms and legs should match. I gave him a yellow and white striped shirt as well. I used the same yellow as my son used to paint his wooden brother.

5. Since I had to paint Earl’s face purple, I decided his arms and legs should match. I gave him a yellow and white striped shirt as well. I used the same yellow as my son used to paint his wooden brother.

6. I copied Earl’s face very carefully from Ben’s drawing. I used wood screws for his hair.

6. I copied Earl’s face very carefully from Ben’s drawing. I used wood screws for his hair.

7. Luckily, I had some velcro. Here is Earl stuck together, ready for my presentations.

7. Luckily, I had some velcro. Here is Earl stuck together, ready for my presentations.

And here are the two wooden brothers, friends!

The schedule is finally set. May 5-11, 2012 I’ll be touring in Ontario with Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week and Middle of Nowhere.

The schedule is finally set. May 5-11, 2012 I’ll be touring in Ontario with Jasper John Dooley, Star of the Week and Middle of Nowhere.

Monday and Tuesday – Ottawa

Wednesday – Toronto

Thursday – Collingwood and Meaford

Friday – Thornbury

See you soon, Ontario kids!

The talented and generous writer and blogger Sara O’Leary has posted an interview with me on her kidlit blog 123oleary. Thank you Sara!

The talented and generous writer and blogger Sara O’Leary has posted an interview with me on her kidlit blog 123oleary. Thank you Sara!

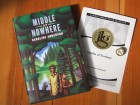

What a surprise to receive a padded envelope in the mail containing… nice things! Here is my certificate and my Junior Library Guild bling, a shiny gold lapel pin. Thanks so much to the JLG folks.

What a surprise to receive a padded envelope in the mail containing… nice things! Here is my certificate and my Junior Library Guild bling, a shiny gold lapel pin. Thanks so much to the JLG folks.